The conversation around artificial intelligence has become increasingly superficial. Every marketing pitch, tutorial, and LinkedIn post seems to focus on the same surface-level advice: write better prompts, use the right keywords, add more examples.

Yet beneath this noise lies a set of principles that genuinely transform how AI systems perform.

After months of working with large language models in various contexts, I’ve discovered patterns that most people simply don’t discuss, because they challenge the standard way we think about prompting.

The revelation that changed everything was understanding that AI doesn’t just take your words at face value. It mirrors the structure of your thinking.

This insight alone reshapes everything you thought you knew about getting quality outputs from these systems.

The Model Copies Your Mental Structure, Not Your Words

When people struggle with AI outputs, they often blame the tool. The reality is far more interesting: the model is faithfully reproducing the organizational structure of your input, regardless of the actual language you use.

Consider what happens when you ask an AI a vague question. You get a vague answer back. This isn’t random. The model has no clear roadmap to follow, so it defaults to surface-level pattern matching. But the moment you introduce structure, something shifts.

If you write something like “First analyze the problem context, then break it into components, then evaluate each component, then synthesize a recommendation,” the output quality changes dramatically. Not because the model became smarter, but because it now has a blueprint to follow.

Think of it this way: if your thinking is scattered across multiple ideas without clear connections, the model picks up on that fragmentation and reproduces it.

If your thinking is hierarchical, with clear progression from foundational concepts to conclusions, the model learns that structure too. This isn’t magic. It’s the model using the patterns in your prompt as a template for how to organize its response.

I’ve tested this across different types of tasks, and the pattern holds every time. A well-organized prompt that walks through a logical sequence produces better results than a longer, more detailed prompt that lacks internal structure.

The level of improvement is not marginal, either. The difference between a chaotic prompt and a structured one can mean the gap between a useless response and something genuinely valuable.

The implications are significant. It means that learning to think in clear steps isn’t just about being a better communicator.

It directly improves the AI’s performance. The skill of breaking down problems methodically becomes the skill of getting better AI outputs.

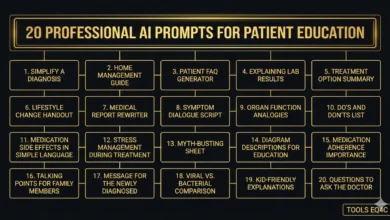

Asking the Model What It Doesn’t Know Increases Accuracy

This principle sounds counterintuitive at first, but it demonstrates something fundamental about how these models operate.

When you ask an AI to list the information it might be missing before it attempts to answer your question, something unexpected happens: the model becomes more cautious, more accurate, and more willing to correct its own assumptions.

The typical approach is to ask for an answer directly. The improved approach is to add a step:

“Before answering this, list three pieces of information you might be missing to fully address this question.”

Then ask for the actual answer.

What’s happening in that pause is that the model is forced into a mode of introspection. It’s identifying gaps in what it knows. It’s acknowledging uncertainty. And once it does that, its subsequent reasoning becomes more disciplined.

It stops hallucinating facts to fill those gaps. It starts qualifying its statements. It becomes aware of its own limitations within the context of the task.

This is relevant beyond the AI world. Humans should probably do this too. Before making recommendations or decisions, explicitly listing what you don’t know yet creates a different quality of thinking.

It’s a form of epistemic discipline that technology companies, consultants, and researchers often skip. Yet it’s one of the highest-leverage interventions for output quality.

The model, it turns out, is better at reasoning when it first acknowledges the boundaries of what it can know. It’s a reminder that pretending to know everything is a weakness, not a strength.

Examples Teach Decision Logic, Not Style

Most people use examples in prompts to show the model what format or style they want. That’s part of it. But the deeper function of examples is teaching the model how you think through problems.

When you provide one or two carefully chosen examples of how you approach a task, something unusual happens.

The model doesn’t copy your voice or your specific word choices. Instead, it begins to absorb your decision-making framework. It learns what you prioritize.

It learns what you consider important enough to mention and what you gloss over. It learns the order in which you evaluate factors.

This is why few-shot prompting works so well for specialized tasks. You’re not teaching the model new facts.

You’re teaching it the logic of your domain, the priorities of your field, and the reasoning pathway you use to navigate decisions.

The practical implication is that the quality of your examples matters far more than the quantity.

One well-chosen example that walks through your actual reasoning beats five generic examples that show correct answers without explaining the thinking behind them.

This is also why few-shot examples work better when you show edge cases or difficult scenarios, not just the straightforward cases. When the model sees how you handle a tricky situation, it learns more about your logic than when it sees obvious decisions.

Breaking Tasks Into Steps Is About Control, Not Just Clarity

People often treat prompt chaining and task decomposition as advanced workflow techniques, something you do when your problem is complex enough to warrant it. This misses the actual mechanism at work.

Breaking tasks into smaller steps is fundamentally a method for preventing the model from hallucinating. It’s about creating checkpoints.

At each checkpoint, the model has to deliver an intermediate result that you can validate or refine before it proceeds to the next step. This architecture stops the model from inventing information to fill gaps.

Think about what happens when you ask an AI to do something complex in one shot. The model needs to predict outputs for multiple steps simultaneously.

If it’s uncertain about step two, it might just invent something plausible to move forward. By the time it reaches the final output, it’s layered several layers of potential hallucinations on top of each other.

Now consider what happens when you force it to complete step one, deliver that result to you, you validate it or adjust it, and only then ask it to proceed to step two.

The model can’t hallucinate step two to compensate for problems in step one, because step one is already locked in. Each step acts as a real constraint on what comes next.

This is why prompt chaining, despite sounding fancy, is actually an operational necessity for producing reliable results.

It’s not optional for high-stakes work. It’s the difference between a system that produces outputs and a system that produces trustworthy outputs.

Constraints Matter More Than Instructions

Here’s where conventional wisdom falls apart. If you tell an AI to write an article, you get an article. If you tell an AI to write an article that’s clear and concise, you get something marginally better.

But if you tell an AI to write an article that a human editor couldn’t shorten by more than ten percent without losing meaning, something different happens.

The second and third approaches are not simply variations on a theme. They represent a fundamental shift in how the model approaches the task.

The constraint forces the model into a tighter mode of operation. It can’t afford to be verbose because it has to hit a specific target. It can’t include fluff because fluff is the first thing cut when you’re trying to minimize words while keeping meaning.

Real constraints force real quality. An AI writing within strict constraints produces tighter work. An AI told to prioritize readability over comprehensiveness changes what it chooses to include.

An AI told that the output will be evaluated by specific criteria structures its response around those criteria.

The lesson here extends beyond prompting: specificity in constraints produces better results than generality in instructions. Tell someone to be creative and you get variation.

Tell someone to solve a specific problem within a narrow budget or timeframe and you often get genuine innovation, because the constraints force real tradeoffs.

Custom GPTs Aren’t Agents, They’re Memory Stabilizers

There’s been a lot of hype around custom GPTs as if they’re some kind of autonomous agents that will work on your behalf.

This misunderstands what they actually are and what makes them valuable.

A custom GPT is fundamentally a memory stabilizer. Its real power isn’t autonomy or intelligence, it’s that it stops forgetting.

You upload your documents, your frameworks, your examples, your preferred outputs, and you build a version of the model that remembers how you work.

Every interaction with that custom GPT has access to that context. The model is calibrated to your way of doing things.

The confusion arises because people expect custom GPTs to do more than what they actually do. They expect them to be persistent agents that carry learning forward between sessions and improve over time.

Currently, custom GPTs don’t have true memory across conversations. Each interaction is essentially fresh, but with your uploaded context as the foundation.

This isn’t a limitation, it’s actually the design. The value is that you don’t have to re-upload your frameworks every conversation. You don’t have to re-explain your priorities and preferences.

The model has them built in. This consistency alone is worth far more than people realize. It’s the difference between a generic AI assistant and one that works in your specific domain with your specific approach.

The implications for how to use custom GPTs are different than people assume. It’s not about automating complex work.

It’s about creating a reference implementation of how you operate, embedded in the model, so that every conversation starts with your context already in place.

Prompt Engineering Is an Operations Skill, Not a Technology Skill

The most interesting trend in how AI is actually being used is this: the people who excel fastest at working with AI aren’t always the people with the most technical training.

They’re often the people who naturally break down problems into clear steps, who think systematically about process, and who have strong communication skills.

This is revealing something important about what prompt engineering actually is. It’s not a technical skill like programming or data science. It’s an operations skill. It’s about structuring work, clarifying requirements, decomposing complex problems, and communicating precisely.

These are the skills that people who’ve spent years in operations, project management, or business analysis already have developed.

A non-technical person who’s spent a decade learning to think in terms of clear workflows and dependencies often outperforms a developer who approaches AI the way they approach code.

The developer looks for clever tricks and optimizations. The operations-minded person focuses on structure and sequence and clarity, which turns out to be what actually makes AI systems work better.

This has major implications for organizations thinking about AI adoption. The people you should be investing in upskilling aren’t necessarily your technical staff. They’re the people who already have strong operational thinking.

They already know how to break work into components, how to sequence activities, how to communicate requirements clearly. Teach them to apply that same thinking to AI interactions and they become surprisingly effective.

It also suggests that the skills most worth developing if you’re entering the AI era aren’t coding skills. They’re the fundamentals of clear thinking: how to break complex ideas into components, how to structure information hierarchically, how to communicate so precisely that there’s no room for misunderstanding.

These are the durable skills that will remain valuable regardless of how the technology changes.

What Actually Changes When You Apply These Principles

Putting these ideas into practice doesn’t require buying new tools or learning new platforms. It’s fundamentally about changing how you think about the interaction with the model.

Start with the structure. Before asking the model a question, think about how you would break down the answer if you were solving it yourself. Make that structure explicit in your prompt. You’ll immediately see improved outputs.

Add the introspection step. Before asking for an answer, ask the model what information it might be missing. Build a habit of acknowledging uncertainty before attempting to provide answers.

Pay attention to what information you provide through examples. Make your examples the clearest window into how you actually think about problems, not just what the right answer looks like.

Break your work into checkpoints. If you’re asking for something complex, ask for intermediate steps first. Validate each step. Only proceed to the next step after you’re satisfied with where you are.

Introduce real constraints. Instead of asking for something with general quality criteria, specify the constraint that actually matters. Make the model operate within boundaries that force quality tradeoffs.

These practices compound. Each one alone makes a measurable difference. Combined, they transform what’s possible with AI systems. They turn a generic tool into a specialized system that produces genuinely valuable work.

The Future Isn’t About Smarter Models

As AI models get larger and more capable, there’s an assumption that the work of prompting will become easier. The models will understand us better, require less structure, need fewer examples. Maybe.

But the people doing the best work with current models aren’t waiting for that. They’re not hoping that future models will somehow read minds and work without clear input. They’re building operational structures that force clarity and discipline into how they work with AI.

They’re treating the model as a reasoning partner that needs structure to do its best work, not as a tool that should figure out what they meant.

The advantage these people have won’t disappear as models improve. If anything, it will compound. Better models working with clear structure and disciplined thinking will produce even better results than the current generation already does.

The real shift in AI isn’t about the technology getting smarter. It’s about people learning to think more structurally, more precisely, more systemically. The technology is just revealing which of these thinking skills actually matter.

That’s the insight that most people are missing. AI isn’t changing what good thinking looks like. It’s exposing what good thinking is by refusing to work well with anything less.